Magit is an interface to the version control system Git, implemented as an Emacs package. Magit aspires to be a complete Git porcelain. While we cannot (yet) claim that Magit wraps and improves upon each and every Git command, it is complete enough to allow even experienced Git users to perform almost all of their daily version control tasks directly from within Emacs. While many fine Git clients exist, only Magit and Git itself deserve to be called porcelains. (more)

Almost everything you see in a Magit buffer can be acted on by pressing some key but that’s not obvious from just seeing how Magit looks, so the screenshots are accompanied by text explaining how what you see can be used to perform a variety of actions.

Regardless of where in a Magit buffer you are, you can always show more details about (or an alternative view of) the thing at point without having to type or copy-paste any information to feed it to some command, as you often would have to do on the command line.

If you came here for images, not a wall of text, then fear not, further down there are more images and less text. And of course you can also just scroll through and ignore the text.

If you came here for moving pictures, then check out the screencasts.

Eventually you might also want to consult the manual. It is quite a useful resource if you are sufficiently proficient in both Git and Emacs. If that’s not the case yet, then stay here for now.

And if any of these resources whet your appetite but you are not an

Emacs user and are not sure how much Emacs you have to know to be able

to use Magit and how long it would take to learn just enough to become

productive without getting stuck in other parts of Emacs, then you

should read this. [Unfortunately the “just enough Emacs to

use Magit” tutorial does not exist yet. Meanwhile you might want to

try Emacs’ interactive tutorial. Start emacs and then type

Control+h and then t.]

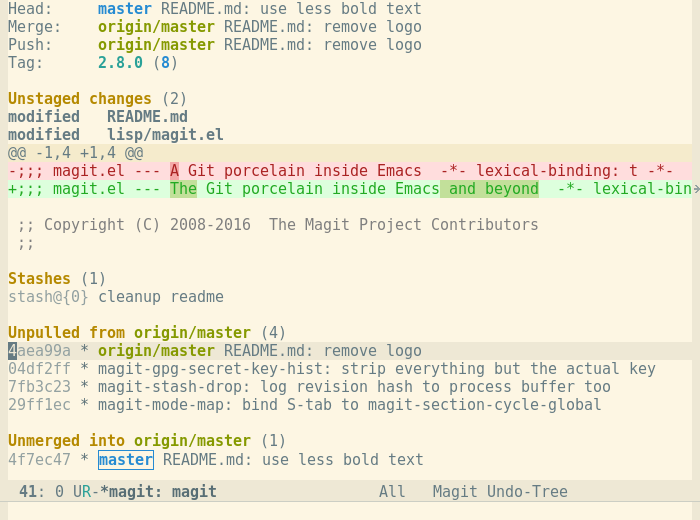

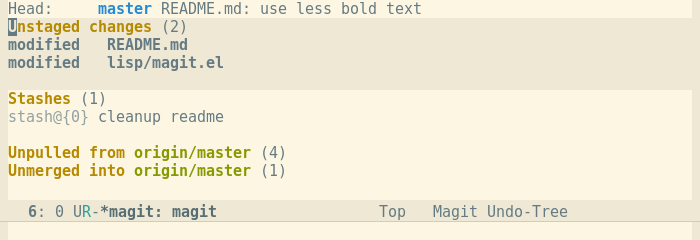

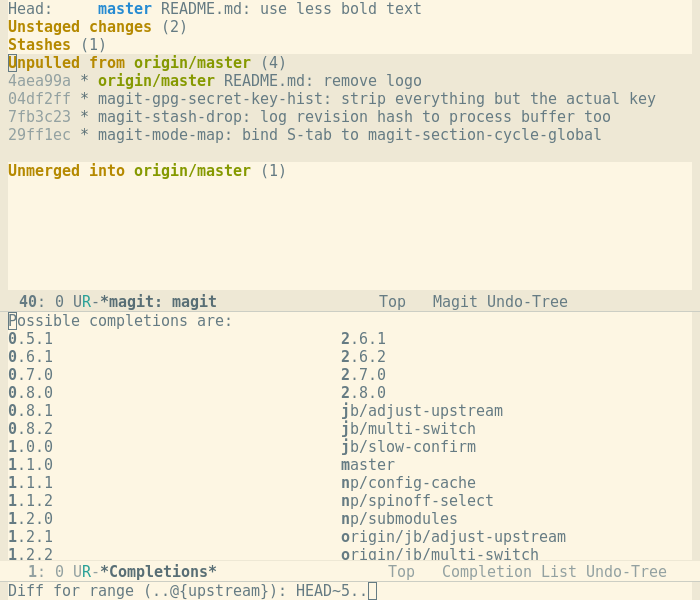

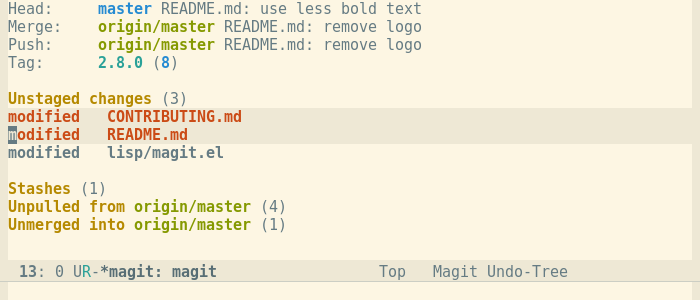

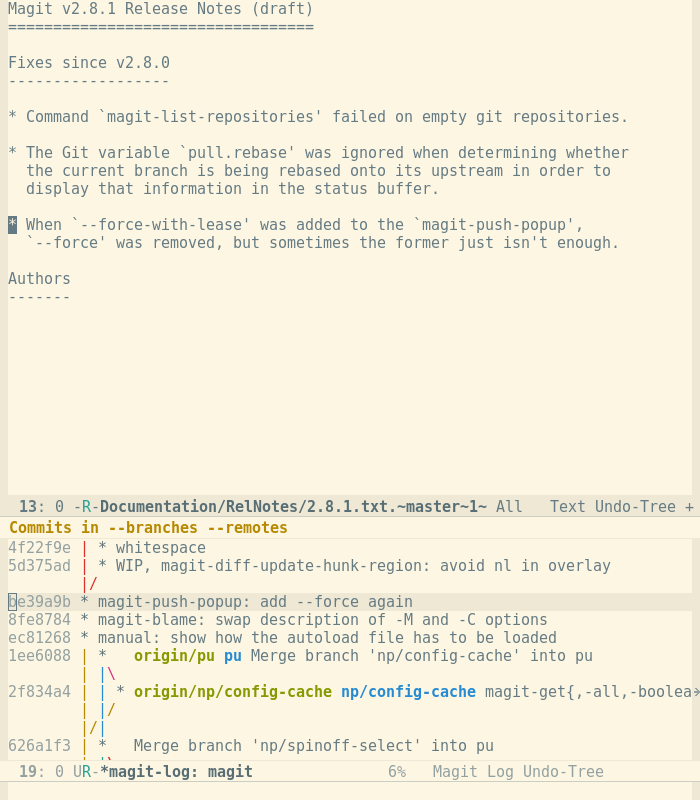

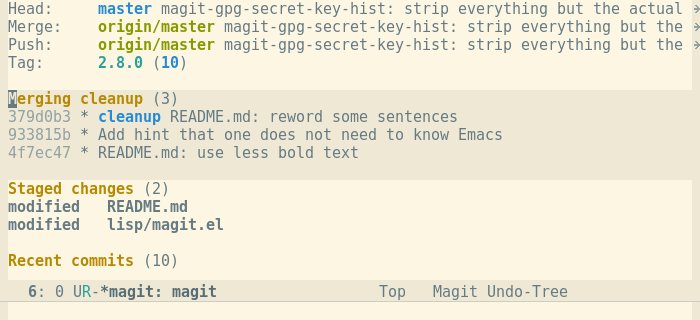

The status buffer, which can be shown while inside a Git repository by

typing C-x g (Control+x followed by g), is

Magit’s equivalent of typing git status in a shell. It shows a

quick overview of the status of the current repository.

As you can see, Magit shows more information than Git. On the command

line you would have to also use git diff, git diff --cached, git

log --oneline origin/master.., and git log --oneline

..origin/master and a few other commands to get the same information.

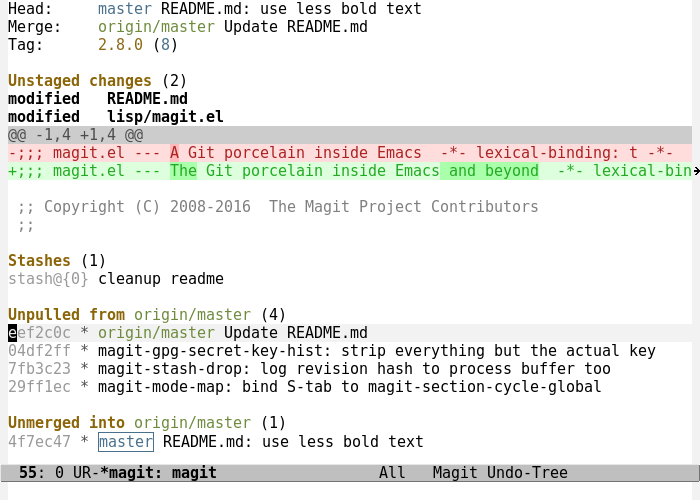

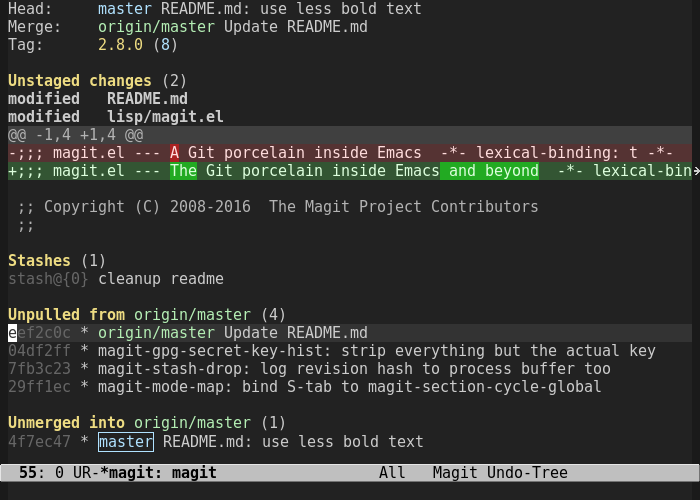

Many themes exist for Emacs. Throughout this guide we use the Solarized light theme, but here is how the status buffer looks when using some other popular themes:

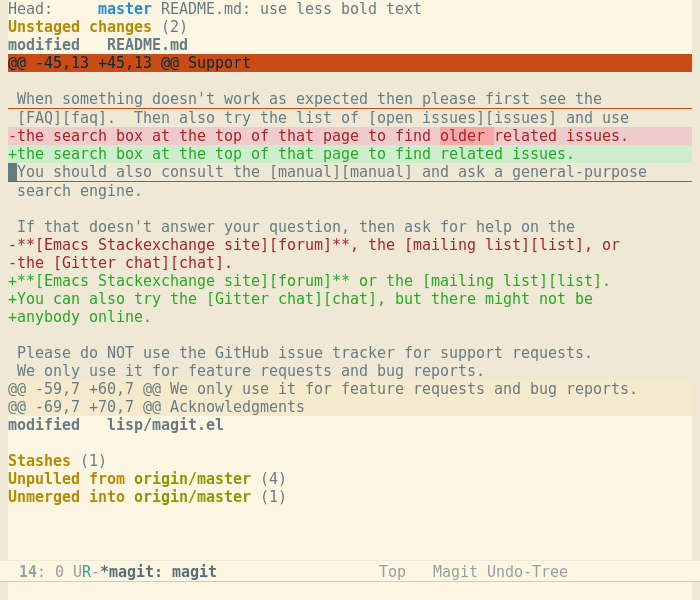

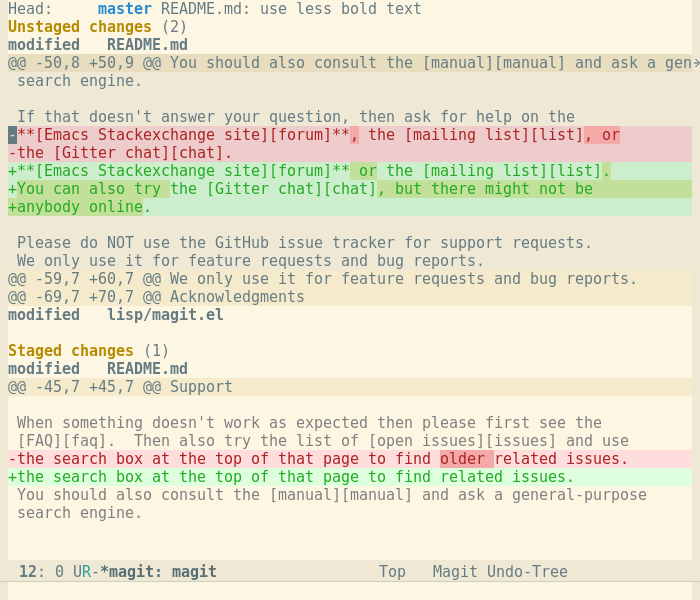

You might have noticed that some diff hunks, those for README.md,

are not shown. That’s because the respective sections have been

collapsed. You can collapse diff sections and any other section

(which are larger than a single line) by moving the cursor into it and

then pressing TAB.

Note that the current section is highlighted by changing the

background color, so that you always know the extent of the current

section. If you moved up one line then “Unpulled from origin/master”

would become the current section and the current line as well as all

the commits that follow would be highlighted, i.e. all commits that

have not been pulled from origin/master yet.

If you don’t currently need to know any details about the unpulled

commits, then you could now type TAB. After doing so you still

see the name of the upstream branch and how many commits it is ahead

of master, but the details, i.e. the individual commits, are hidden.

If you want to see them just type TAB again; on the command

line you would have to type something like git log --oneline

..@{upstream}.

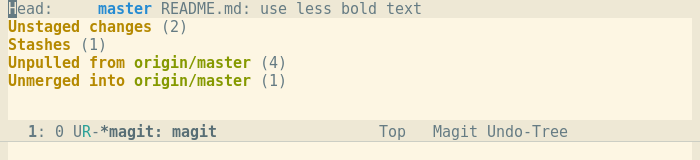

In Magit’s status buffer you can always show as much or little as currently appropriate without having to remember both the command that shows little or much information. Instead you can temporally hide or show details as needed by pressing a single key.

After hiding as much as possible you would see this instead:

Or you might want to see a little more than that, e.g.:

If you use Magit to perform some action such as staging a change, then

the status buffer is automatically updated. This can also be triggered

on file save by using

magit-after-save-refresh-status.

And if you change something outside of Emacs, then you can press g to refresh the status buffer or G to refresh all Magit buffers.

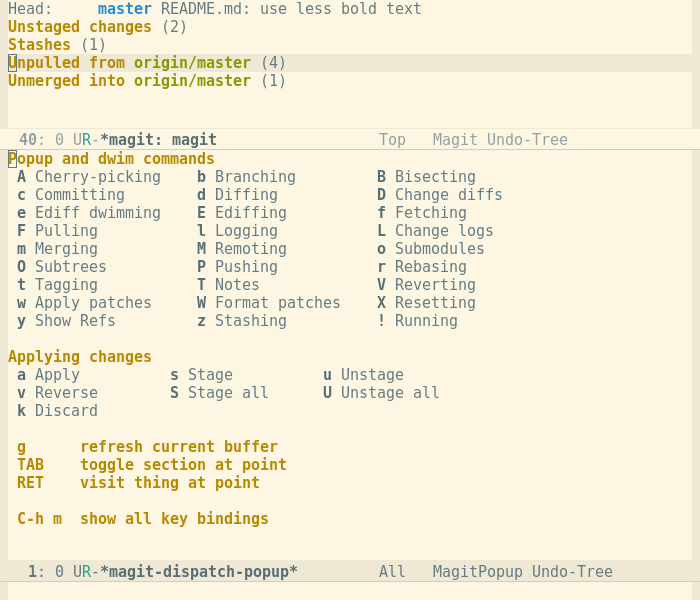

A major advantage Magit has over Git on the command line is that nearly everything you see in a Magit buffer can be acted on. Hiding and showing a section is just one example of that.

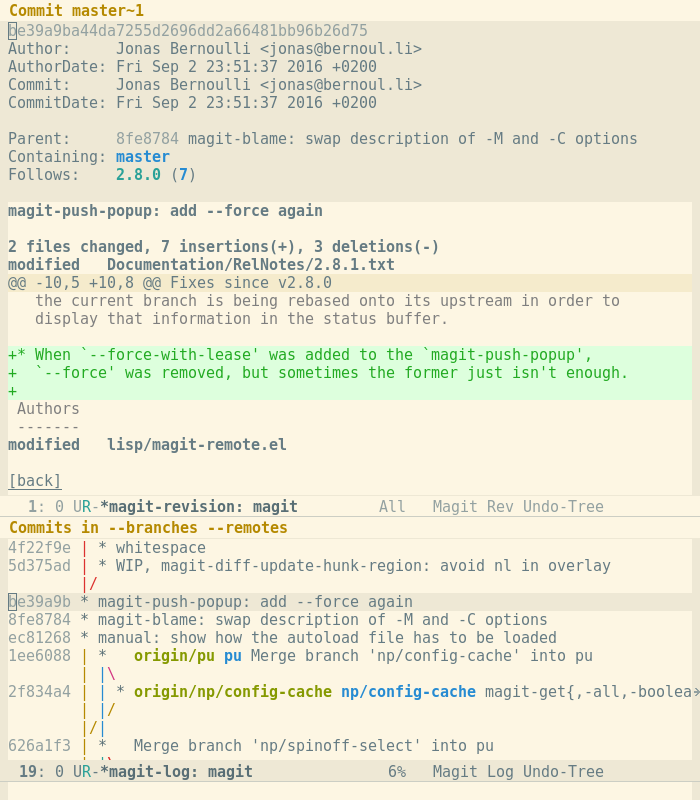

Beside TAB, another key that works nearly everywhere is RET (return). It shows a more detailed view of the thing at point, be that a commit, branch, diff, hunk, stash, …

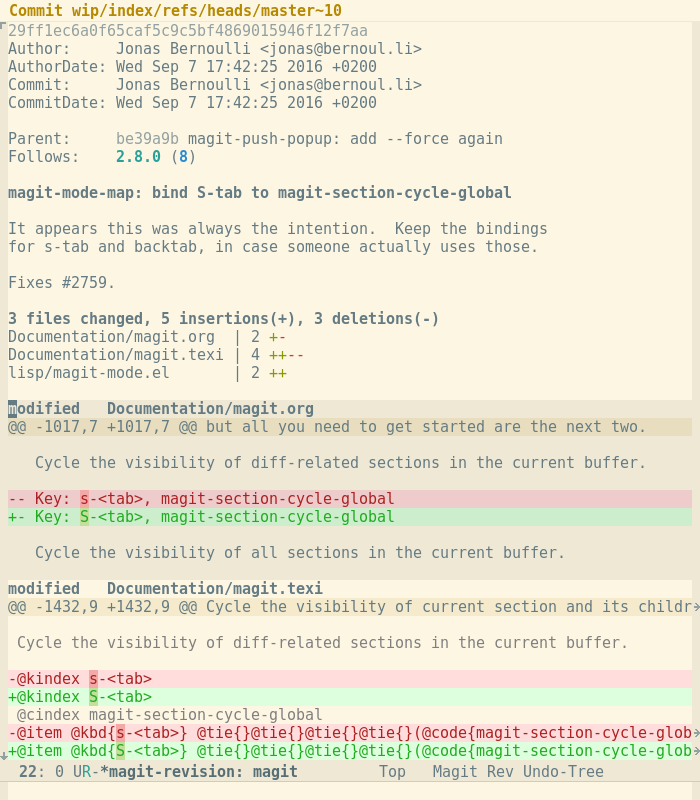

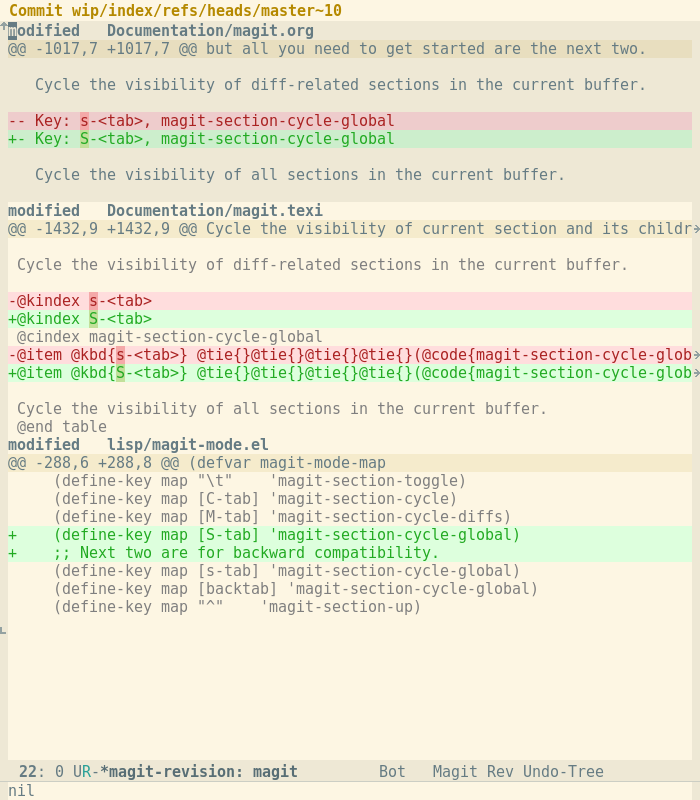

For example if you type RET while the cursor is on a commit, then the commit details are shown including the commit message and the diff.

In this case the diff does not completely fit into the window. You could hide some sections - the metadata, commit, and diffstat at the top - to bring the complete diff into view, or you could move down a few sections to view the rest of the diff.

The basic keys movement keys are C-p to move up one section, and C-n to move down one section. M-p (i.e. Meta+p, also commonly known as Alt+p) and M-n would move to the previous or next section on the same level as the current section. The latter two commands can be used to navigate Magit buffers more quickly by skipping child sections, e.g. you could jump from one file to another without having to step through the hunks of the first.

Or if you were only interested in the diff but not the commit message in the first place, you could have typed d d (d by itself and then d again) in the status buffer instead of RET.

But you already pressed RET, now what? Type q to quit (i.e. hide) the current Magit buffer, in this case the commit buffer, to go back to the previous buffer (more precisely the previous window configuration). In this case that would take you back to the status buffer.

So while RET performs the most likely action for the section by showing a focused more detailed view of the thing at point, there are many other keys which perform other, equally useful actions. There is d to show a diff, l to show a log, and dozens more, some of which will be mentioned below.

If the cursor is on the thing you want to act on, then it is very convenient that many commands default to acting on that thing. But sometimes you do want to act on some other thing. It might be inconvenient to first having to move to its representation in the current buffer, or the thing you want to act on might not even be present in the current buffer. Many commands therefore also allow you to act on some other thing.

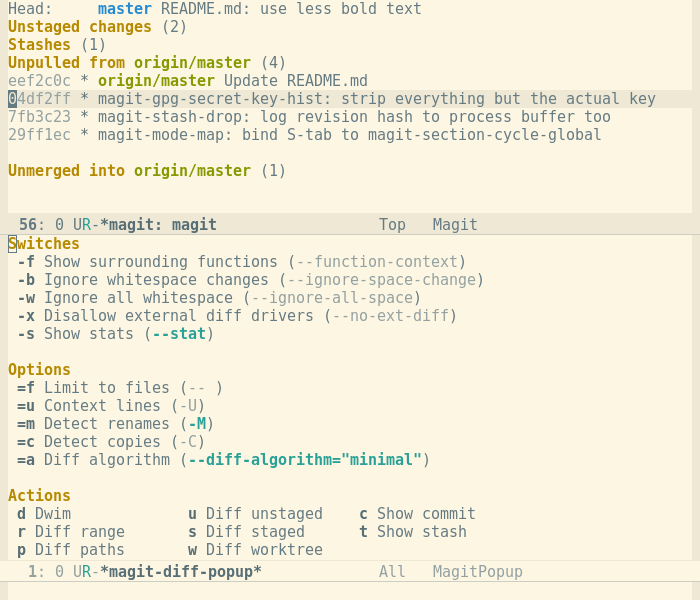

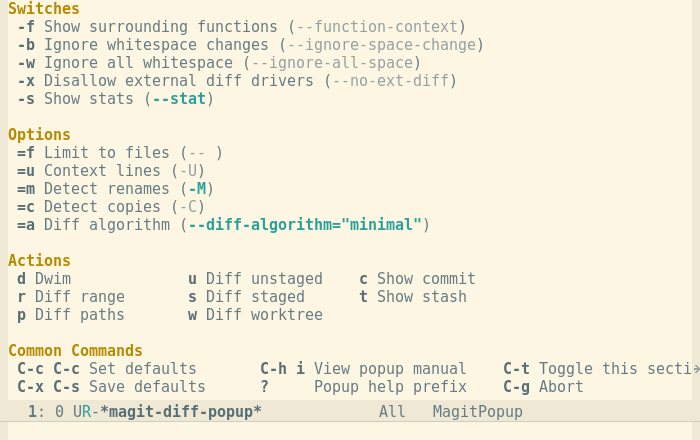

Above we pressed d twice to show the diff for the commit at point. Pressing d just once actually does something by itself, it shows the “diff popup”, which you can see below.

The window is split into two panes. (Note that in Emacs, which predates window systems, one would say the frame is split into two windows.) The pane at the top still shows the status buffer, while the pane at the bottom shows the diff popup.

The diff popup shows some actions at the bottom and some arguments, which you know from your command line use of Git, at the top.

Previously we pressed d again. That causes the popup buffer/window to disappear and the “dwim” (do what I mean) diff variant to be invoked. As with most dwim variant, this particular one acts on the thing at point. But alternatively you could press s to show the index, for example.

Or you might want to show the diff for an arbitrary range, in which case you would press r. After doing so you can type the range with completion:

Many popups do not only offer actions, but also allow users to set arguments which will then be used when the invoked action calls Git.

In the diff popup, for example, one can enable the use of the

--function-context argument by typing - f before invoking an

action. When an argument takes a value, then that is read from the

user, when appropriate with completion.

Usually arguments are just used ones, when you later enter the same popup again, then it is not enabled anymore, but it is possible to save the arguments you want to be used by default.

To do so enter the popup, set the arguments as desired, and then instead of invoking an action, type C-c C-c to save them as the default for the current popup. These settings persist between Emacs sessions.

C-c C-c is only one of the commands that is available in all popups. To show them all, type C-t.

Many Magit commands are invoked by first showing the available variants and then picking one of those variants. For many, but not all, popups it is possible to press the same key twice to invoke the most common variant, often a dwim variant.

But there are also many commands which are not implemented using such a popup. We have seen the hide/show command (TAB) and the visit (RET) command so far. Other such commands are staging (s) and unstaging (u), which always act on the file or hunk at point. These and similar commands will be discussed below.

There are many popups but, at least for the most commonly used once, you will quickly learn the keys you have to press because they are mnemonic. But until then, or when you need to do something you rarely do, then the “popup of popups” comes to the rescue. Show it by typing ?.

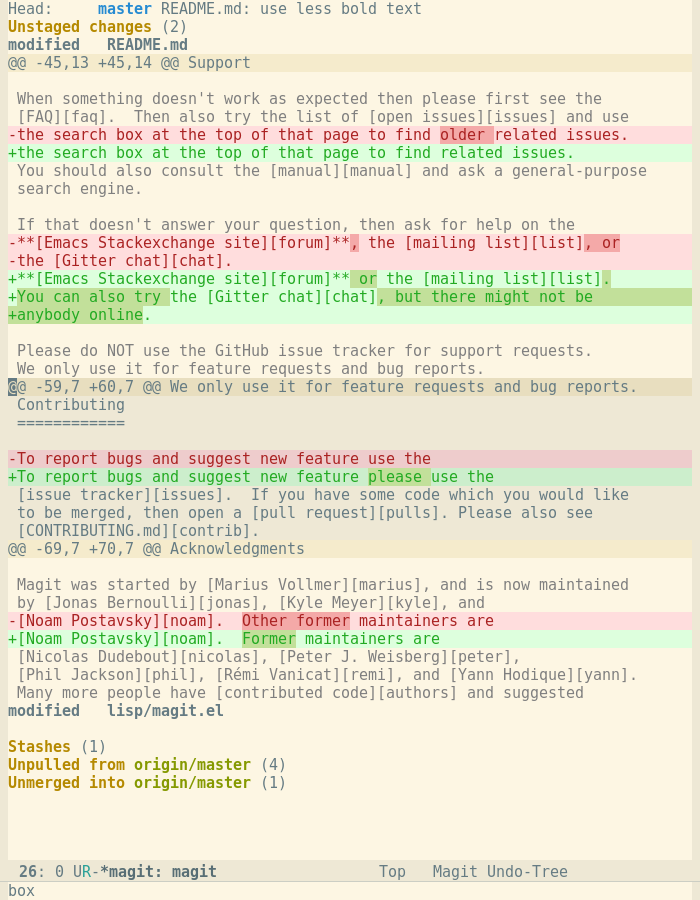

Magit makes it very simple to stage and later commit only some changes, while leaving other changes in the working tree, e.g. to commit them separately.

On the command line you have to invoke special staging and unstaging

sessions using git add --patch or git reset --patch, which is

quite cumbersome as you have to go through all the available hunks one

by one and in order.

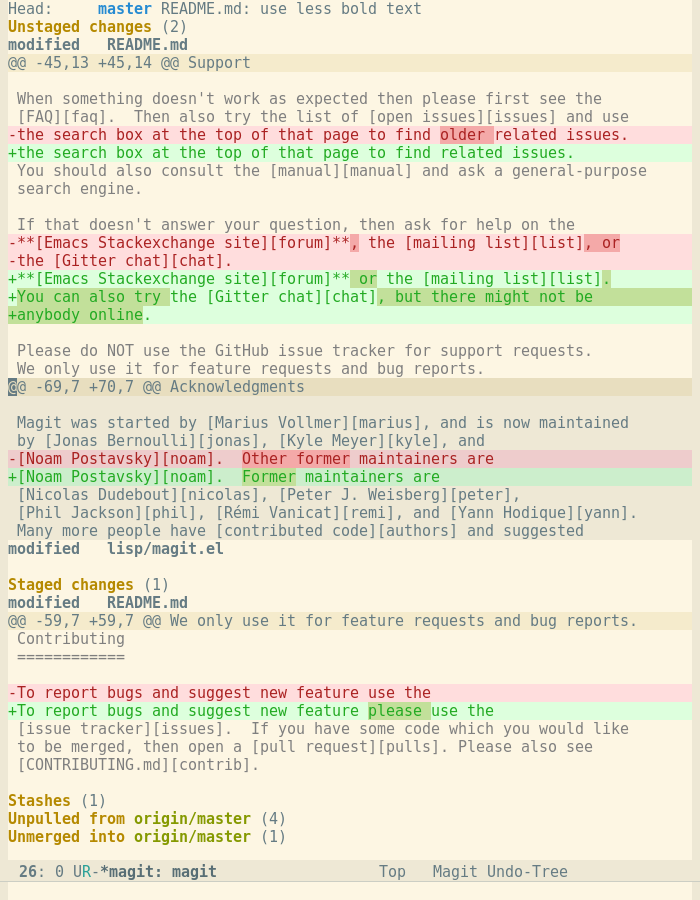

This is an area where it is most useful that Magit allows acting on

all things you can see. To stage only the -59,7 +60,7 hunk you

would move there and simply press s, without having to first tell

Git that you don’t want to stage -45,13 +45,14 and then also that

you don’t want to stage -69,7 +70,7.

After you have done so, the buffer automatically updates and the cursor is moved to the next hunk. Therefore you can stage multiple hunks by pressing s multiple times. If that’s what you want, but if not, then Magit won’t bother you with the other hunks like Git does. The staged hunk now appears inside the “Staged changes” section.

Unstaging of course works the same way, move to a staged change and press u. You can also stage or unstage everything at once by pressing S or U.

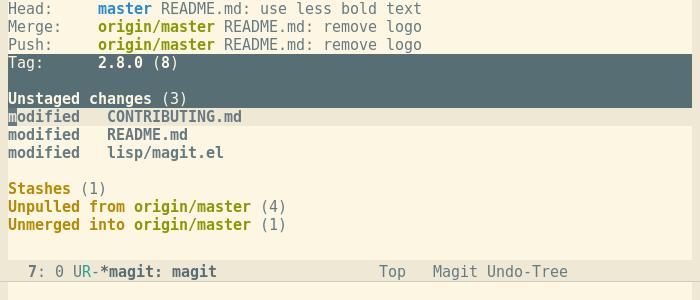

You can also stage multiple files or hunks at once. To do so mark these sibling section using the region. (The region is an Emacs term for “the selected text”.)

First press C-SPC to mark one end of the region and then move

the cursor until you reach what should be the other end of it.

Alternatively you could also use the mouse. If the region constitutes

a valid “Magit selection” which can be acted on as a unit, then it

looks like this, clearly indicating that both CONTRIBUTING.md and

README.md are selected, but lisp/magit.el is not:

Many commands which would normally act on the current section, when such a selection is active, instead act on that selection, i.e. all the marked sections. Staging (s) is such a command.

If a region is active, but it does not constitute a valid selection because the sections that fall into it are not siblings of one another, then the region looks as it usually does in Emacs. That makes it trivial to see if you are about to act on the current section only or on the selection.

Beside sibling selections, Magit supports a second selection, the “hunk internal region”. You can mark just part of a hunk using the region and then only stage (or unstage or otherwise apply) just that part of the hunk.

Here you can see what it looks like when only the part of the hunk which removes the word “older” is selected using the region:

If you pressed s now, then only that part would be staged, resulting in:

(Note how conveniently the cursor is placed. We take pride in such details. This particular detail might not be all that important when looked at in isolation, but we go that little extra step in many places, and that does make a difference.)

Instead of using a hunk internal region to just stage parts of the

hunk, you could also have told Git to make the hunks smaller using

the -U argument. To do so press - until the hunk in question

breaks up into two. Use + to do the opposite.

This works in the status buffer as well as all other buffers that may contain diffs, so far we have seen plain diff buffers and commit buffers.

As we have seen above you can specify several arguments when using the diff popup to create the diff buffer. But when showing the status buffer by pressing C-x g or when showing the commit buffer by pressing RET, then that is not possible. You can however change the diff arguments used in the current buffer. Press D to bring the diff arguments popup. It is very similar to the diff popup in that it offers the same arguments, but instead of actions which show some diff in another buffer, it offers actions which affect the current buffer.

Press g to use the arguments that are currently selected in the popup in the current buffer. s sets these arguments as the default for buffers of the same type, so if you did that in the status buffer of some repository, then the same arguments would be used for status buffers of other repositories that you subsequently create. But this only lasts until you restart Emacs; to permanently save new defaults use w.

A similar “log arguments” popup exists on L.

Some other graphical tools approach Magit when it comes to the staging features described above, but I don’t think any one of them quite makes it. One more thing that sets Magit apart from these tools however, is that these features are not only available for staging and unstaging, but also when “otherwise applying changes”.

With Magit you can also discard, reverse, or apply, the file, files, hunk, hunks, or region at point using the exact same interface as described above. For more information about these apply variants consult the manual.

If you noticed that the diff popup lacked your favorite argument, then fear not. It is trivial to add arguments to an existing popup, as describe in the manual.

Some arguments are missing because they are not actually required.

--cached falls into that category; it’s not needed because to show

the cached changes (those in the index) you simply use the “staged

changes” diff variant, by pressing s.

Other arguments, e.g. --irreversible-delete, are missing because we

have to strike a balance between making every argument available that

anyone might ever need and not overwhelming beginners with arguments

that nobody will ever need.

(I intend to make it possible to optionally show all arguments which could possibly be used in a future release.)

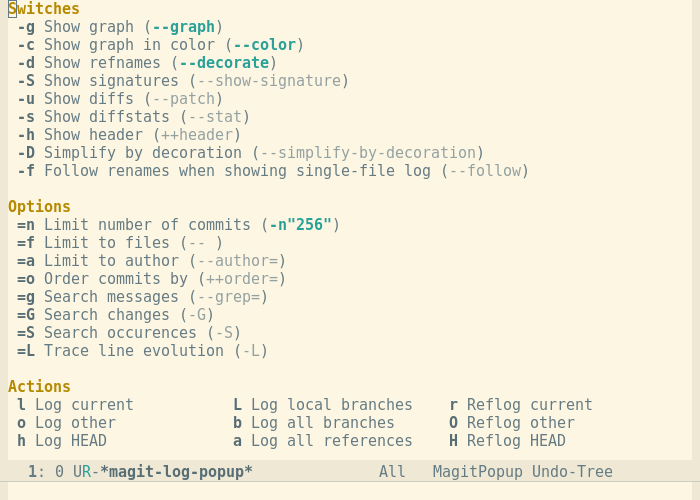

Like it is possible to show a diff in a separate buffer, that is of course also possible for logs. On a branch RET shows the respective log and there also exists a log popup on l, which looks like this:

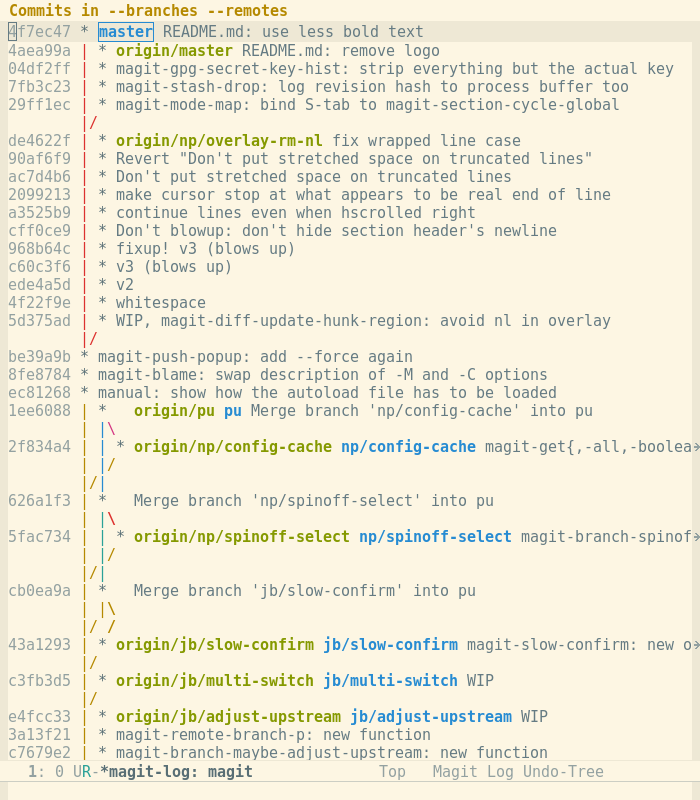

The log buffer itself looks quite similar to what you would get on the command line. Here is an example of the “show all branches” variant (notice the arguments displayed at the top):

But things get more interesting once you press RET to show the commit at point in a separate buffer. Actually in this case it is better to press SPC, that also displays the same buffer but the current log buffer remains the current buffer. If you now move through the log buffer using C-p and C-n, the commit buffer is automatically updated to show the commit which the cursor is on in the log buffer.

The same works if you move through a log buffer and the other buffer contains a blob (a “file as it was at a certain commit”). To create such a blob buffer go to some diff in the commit buffer and press, you guessed it, RET. (Note how this goes to the appropriate location in the blob buffer.) Go back to the log buffer and move around to see the blob buffer being updated.

As we have seen Magit provides commands that allow invoking certain

variant of Git commands without having to remember and type many

arguments. The “show diff for staged” changes, for example, is such

command that saves you from having to remember and type --cached.

That, while useful, isn’t all that innovative by itself though. Also

many experienced users of the Git command line have probably created

aliases for that sort of thing by now.

But Magit also provides many truly innovative commands which go beyond what you could do with aliases. These include, among others, commands for committing, rebasing, stashing, and branching. All of which will be discussed below.

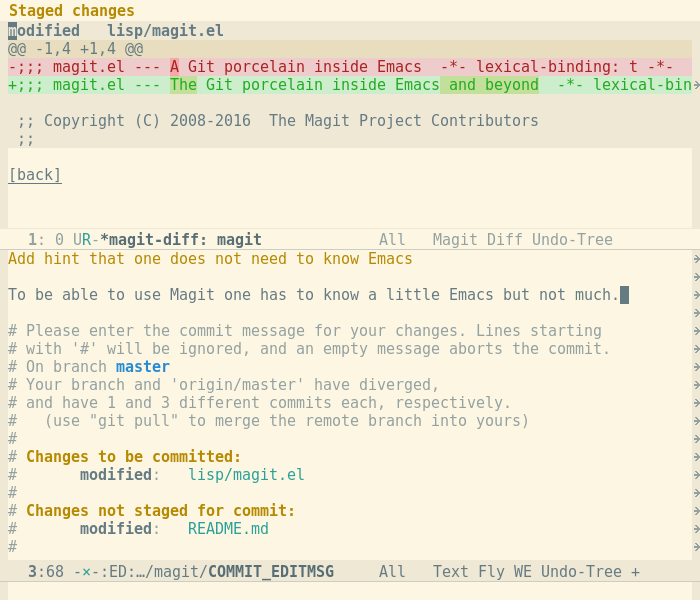

Press c to show the committing popup and then c to

create a regular new commit. This calls git commit and arranges for

the current Emacs session to be used as the $GIT_EDITOR. The commit

message buffer is opened in one buffer and another buffer shows the

changes about to be committed. When done press C-c C-c.

You can also amend to HEAD by pressing a. This is just like

git commit --amend. While editing the message while amending, press

C-c C-d to toggle between showing only the changes that are

being added to HEAD and all changes that will make it into the amended

commit.

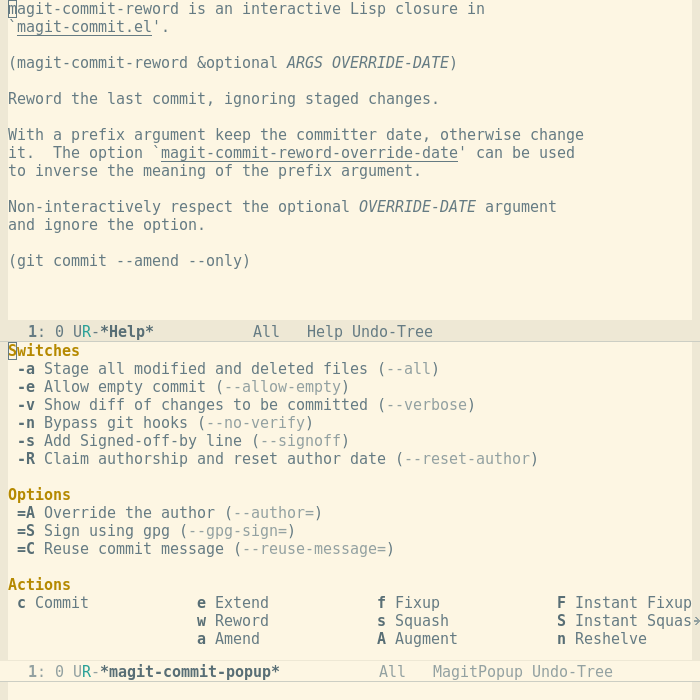

There are also fixup and squash variants. And then there are some variants that don’t exist in Git. Because the terms used here do not correspond to terms you might be used to from Git this might be a good time to show you how to get more information about a popup action or argument. To show information about the “reword” variant type ? and then w, which gives you this:

So “reword” lets you change HEAD’s message without adding any

changes to it. Similarly “extend” adds the staged changes without

forcing you to review the message, which is quite useful for simple

typo fixes.

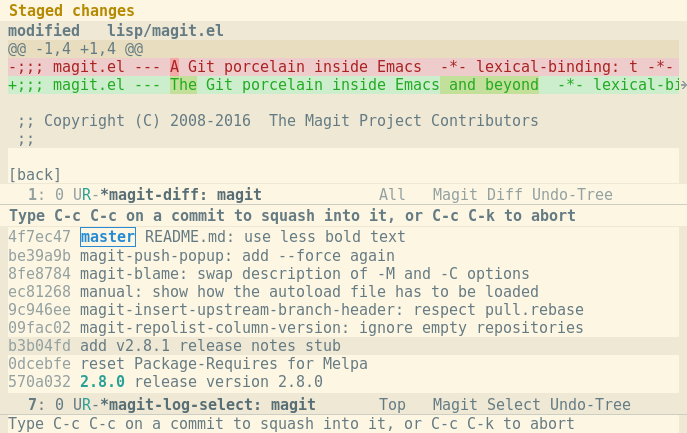

“Instant fixup and squash” let you pick a commit to be modified with

the staged changes, but then they immediately initiate a rebase.

“Instant fixup” is mostly like “extend” but on commits other than

HEAD.

The commit to be modified is picked using a specialized log buffer.

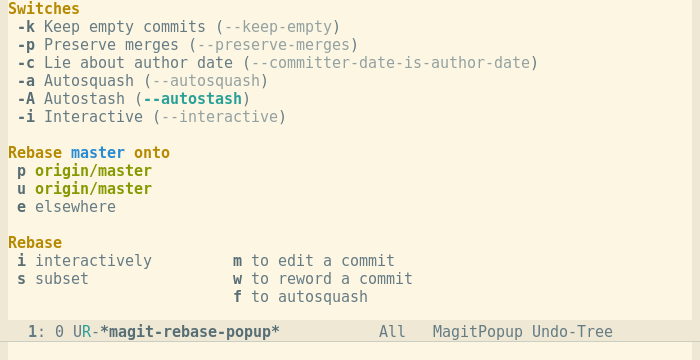

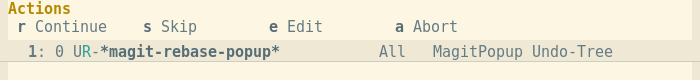

The rebasing popup also provides a variety of commands unique to Magit.

There is one variant which lets you edit a single commit, without having to go through having to edit a list to be rebased. Simply go to the commit you want to rebase in any log, press r to enter the rebase popup, and then m to modify that commit. Likewise there is a variant which allows only editing the message of a single commit.

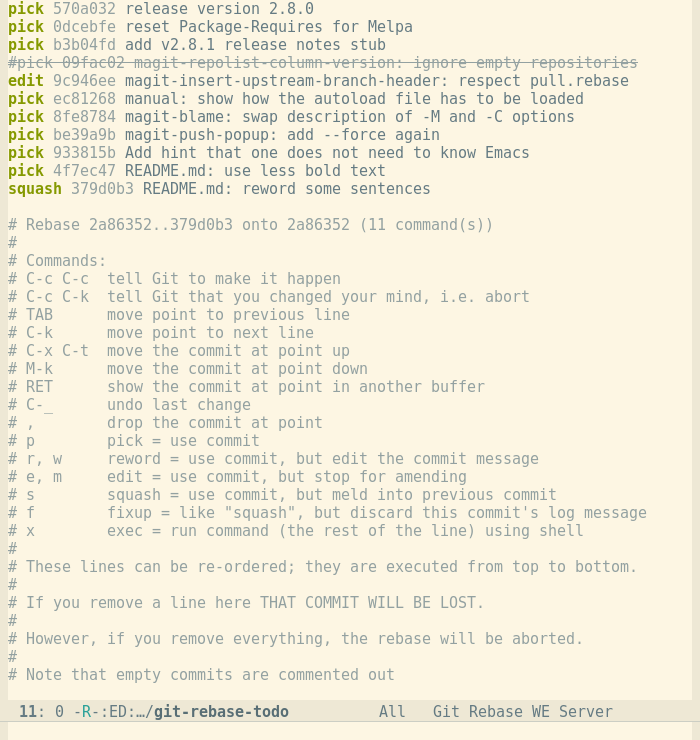

When performing an interactive rebase (which is supposed affect more

than a single commit), then this is done as usual by editing the file

git-rebase-todo, but when using Magit there are a few additional key

bindings and other convenience features available:

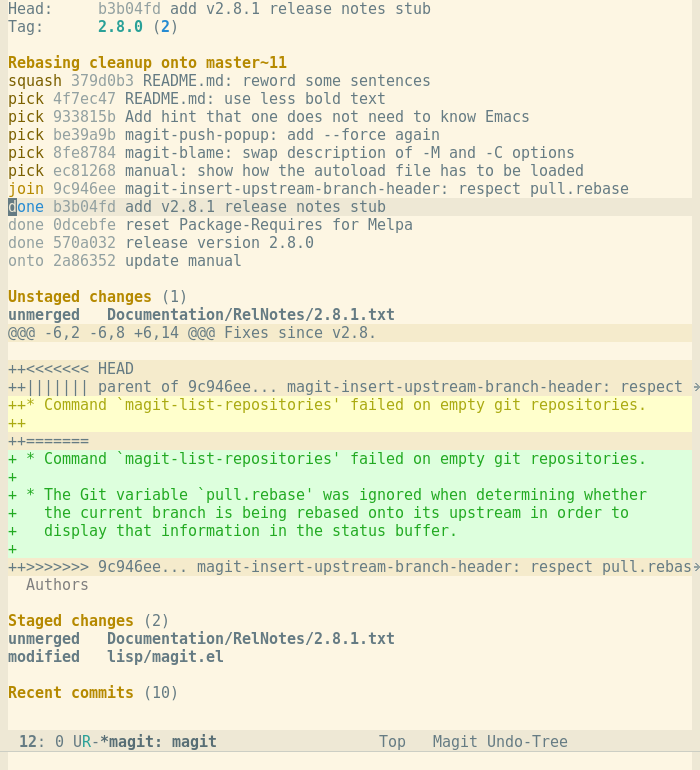

When a rebase sequence is in progress, then a log-like section about that is shown in the status buffer. Like in a regular log, you can of course perform various actions on the listed commits, like viewing them. And of course conflicts are shown too.

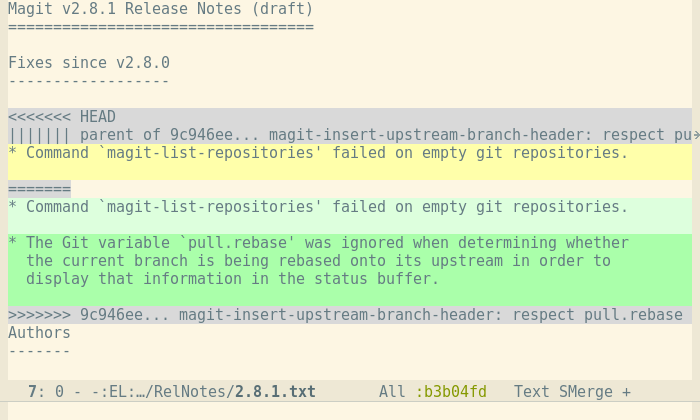

You can resolve the conflict by visiting the file. There you can use the Smerge package to do so in style or you can just edit the file. Or you can use the Ediff package, which shows the two sides and optionally the common ancestor in separate windows. Magit wraps the features provided by these packages, but since they are not actually part of Magit, we skip looking at them in detail. Just so much, after pressing RET on a conflict hunk you would see something like this:

Of course you could also abort the rebase by pressing r again, and then a:

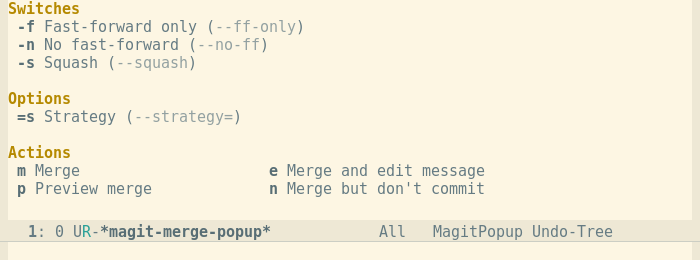

The merging popup is quite simple.

When a merge is in progress then the status buffer shows information about that:

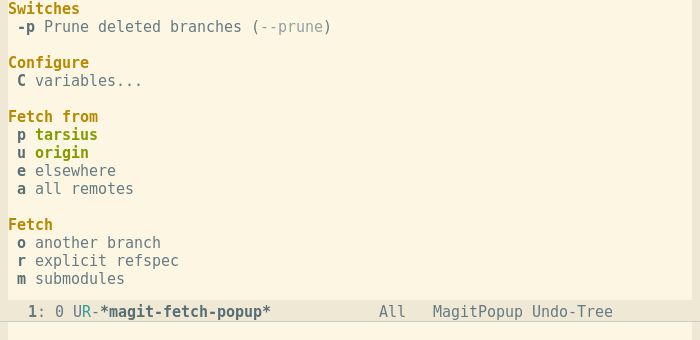

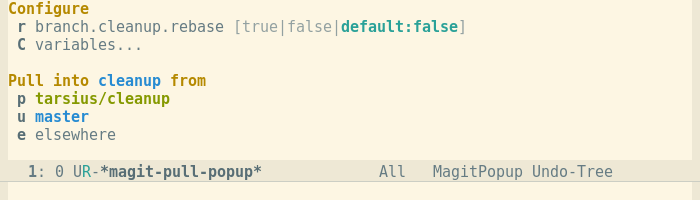

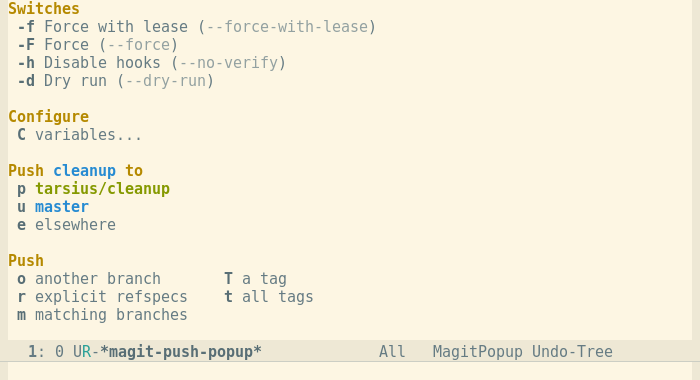

Without going into any details, here are the popups for fetching, pulling and pushing.

One thing worth noting though is that all of these popups feature a “push-remote”, a “upstream”, and a “elsewhere” variant. A branch’s “push-remote” is somewhat similar to the “upstream”, but it usually is a different branch. The “push-remote” is actually a Git feature but not many Git users know about it because it is hardly documented. To learn more about the “push-remote” and how it is different from the “upstream”, see this

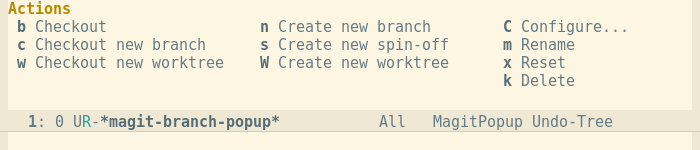

The branching popup is used to edit, create, and/or checkout a branch.

The “create new spin-off” variant is particularly interesting. It

creates and checks out a new branch whose upstream is the previously

checked out branch. Then it rewinds that branch to its upstream.

This is useful when you began working on some new feature directly on

master, and then realize that you should be using a feature branch.

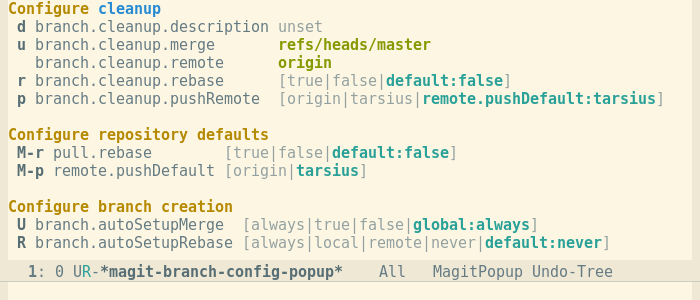

The branching popup is also one of the few popups that have a sub-popup. Press C to show the branch configuration popup.

In that popup you can see the values of some important Git variables concerning the current branch. The values obviously can be changed using the shown keys.

TODO describe

TODO describe

TODO describe

TODO stash etc.

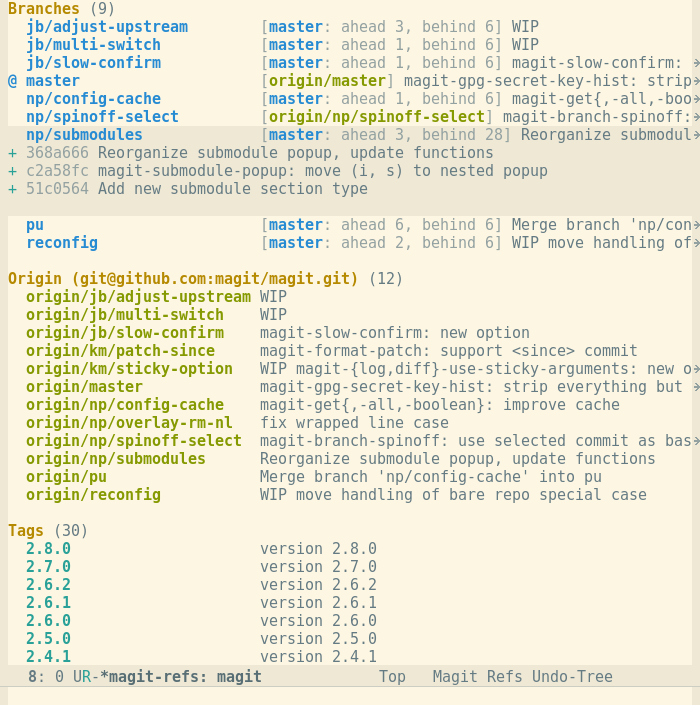

Use y to show branches:

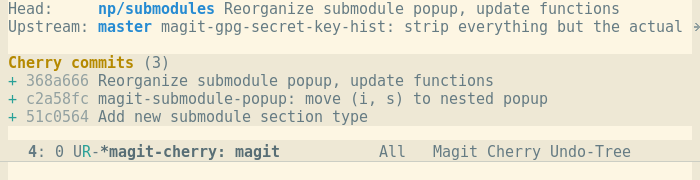

Use Y to show cherries:

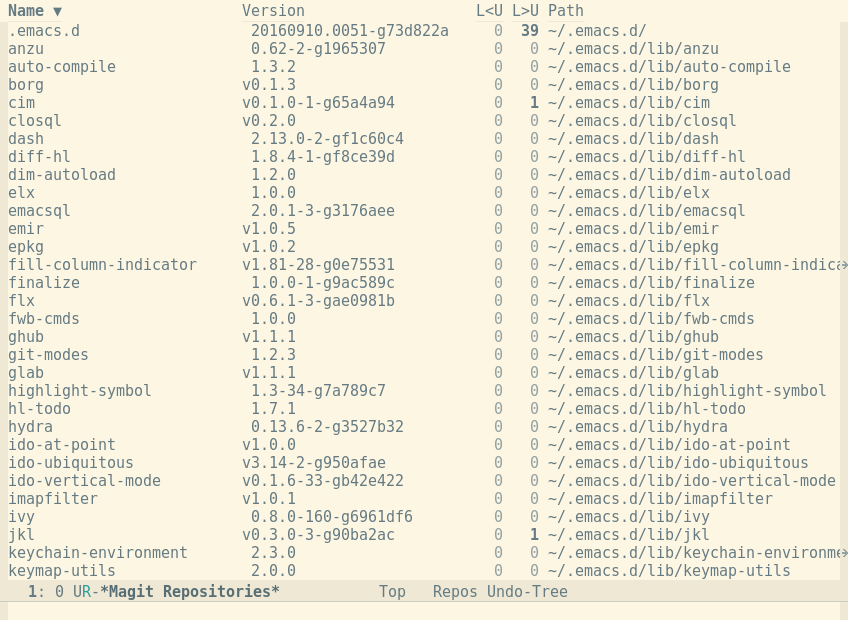

Use M-x magit-list-repositories RET to list local repositories:

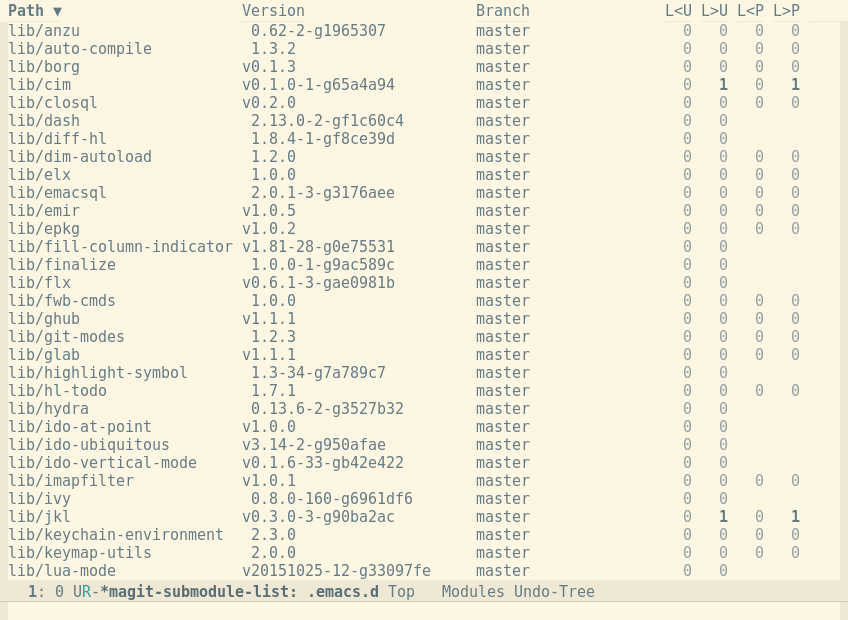

Use M-x magit-list-submodules RET to list submodules:

There are many other popups, including:

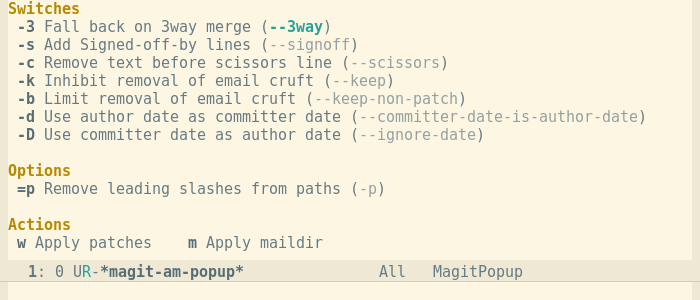

See Maildir Patches.

See Maildir Patches.

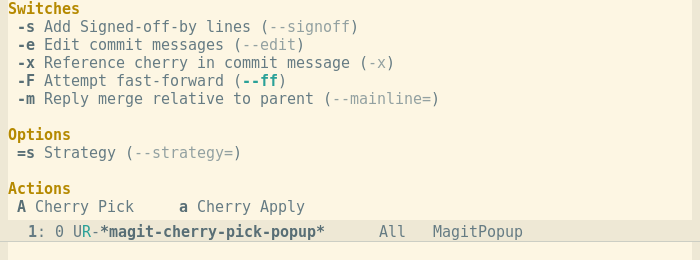

See Cherry Picking.

See Cherry Picking.

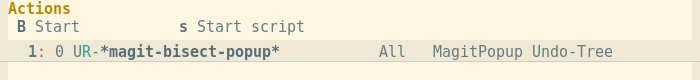

See Bisecting.

See Bisecting.

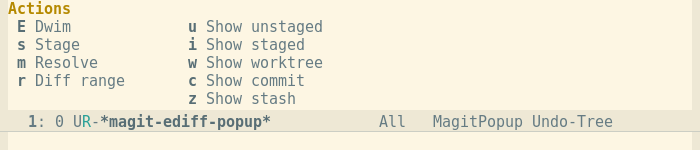

See Ediffing.

See Ediffing.

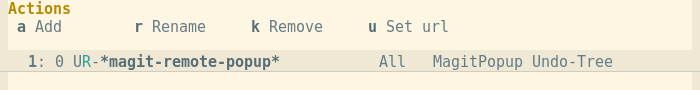

See Remotes.

See Remotes.

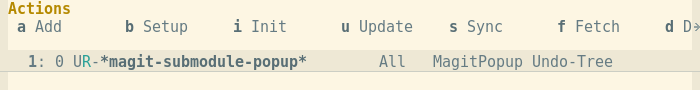

See Submodules.

See Submodules.

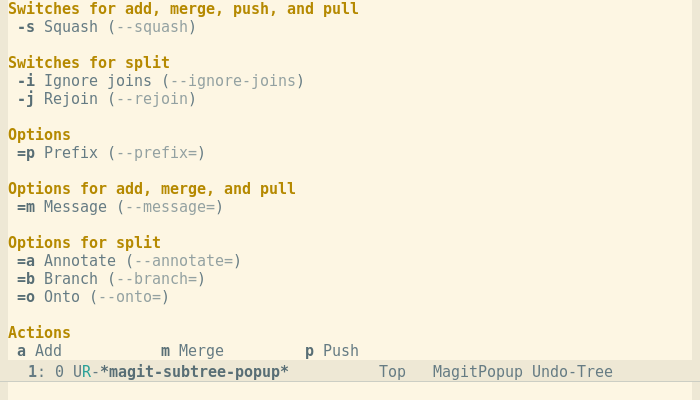

See Subtree.

See Subtree.

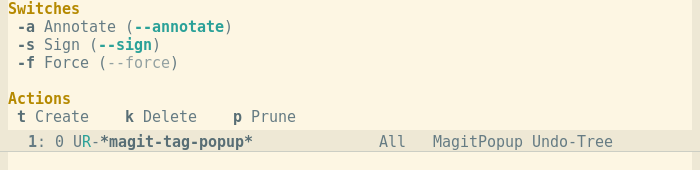

See Tagging.

See Tagging.

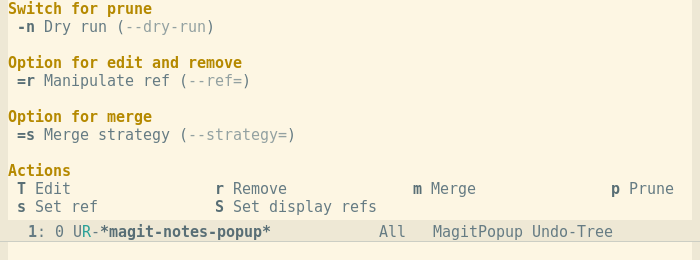

See Notes.

See Notes.

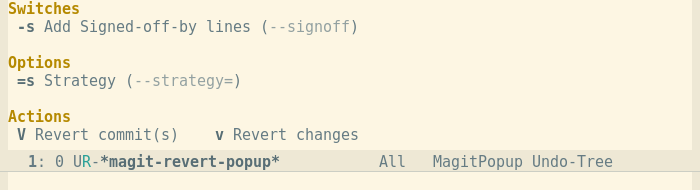

See Reverting.

See Reverting.

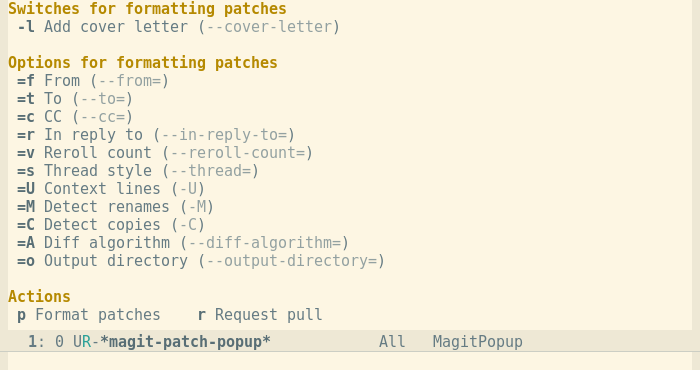

See Plain Patches.

See Plain Patches.

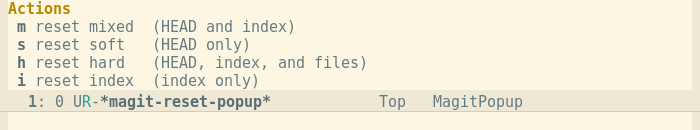

See Resetting.

See Resetting.

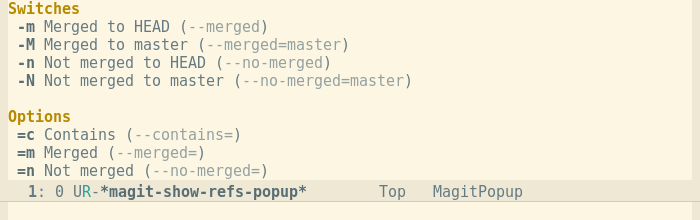

See References Buffer.

See References Buffer.

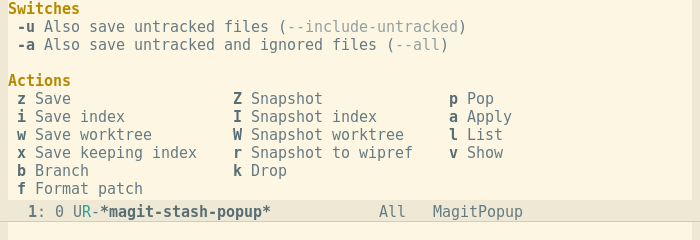

See Stashing.

See Stashing.

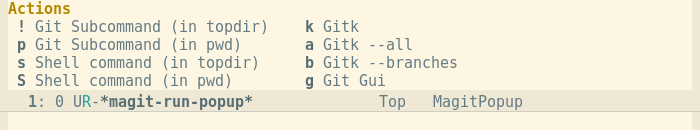

See Running Git Manually.

See Running Git Manually.